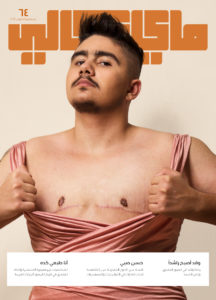

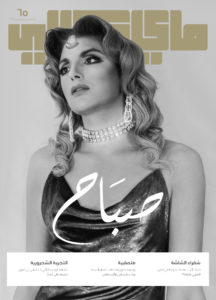

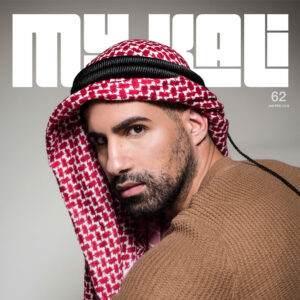

In September 2007, Khalid founded My.Kali (named after his own nickname “Kali”) as a gay Arab men’s online magazine in English. Until today, My.Kali has evolved to cover queer, feminist, and intersexual issues in Arabic and English. In the lead up to the publication’s launch, Khalid had come out to his mom and he was fearful of his sexuality clashing with Jordanian society. However, he and the My.Kali team moved forward with the publication even though they were unaware of laws in Jordan concerning sexuality and media.

In the beginning, the publication was a blog, since in 2007 social media was not the powerful platform it is now. The website was built using Weebly, a free website builder that was chosen because it was free and had ready templates (you can still check the old site here).

The site proved to be a success, and then their social media boomed growing a community of over 51,000 page likes on Facebook and over 11,000 followers on Instagram. When their website was blocked by the Jordanian government, and later blocked in Qatar and Gaza, they relied heavily on their social media accounts. After the site was blocked they started researching hosting options from countries that would not allow their website to be blocked again. This is when they started using Medium to publish English and Arabic content, but they were frustrated with the platform because it does not properly support visuals (multimedia) or posts in Arabic (you can see here their page on Medium).

The look and feel of My.Kali website was always that of an online magazine publication. Khalid described why he chose this format.

He said, “I was definitely inspired by Melody TV, Seventeen magazine, and vintage Vogues, but I was also reading a lot of National Geographic and Newsweek.”

Khalid majored in Graphic Design. He did not study journalism professionally, but he was interested in different publications as a consumer, and his media activist interest grew from there:

Khalid majored in Graphic Design. He did not study journalism professionally, but he was interested in different publications as a consumer, and his media activist interest grew from there: